Along The Gilpin Tramway - A Closer Look

123

123

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Wood Mine.

|

GUNNELL HILL (continued)

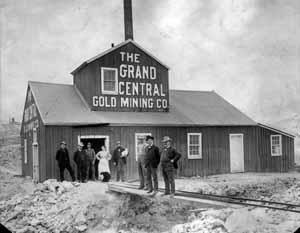

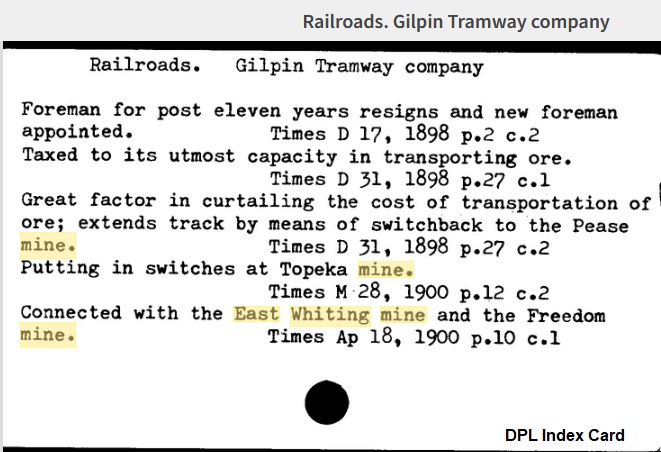

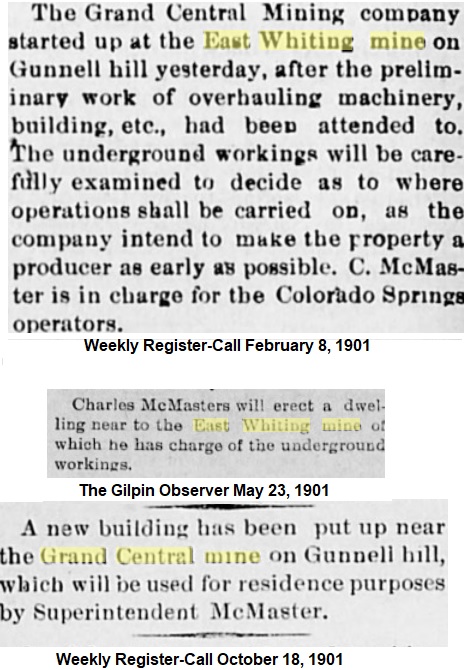

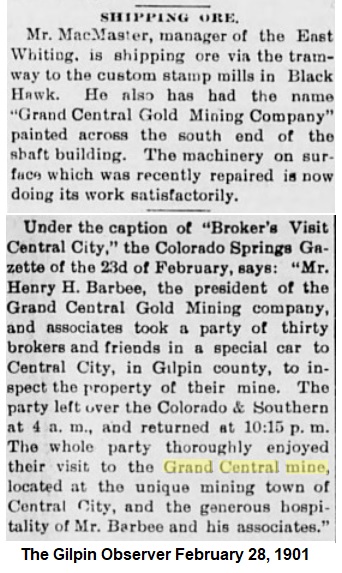

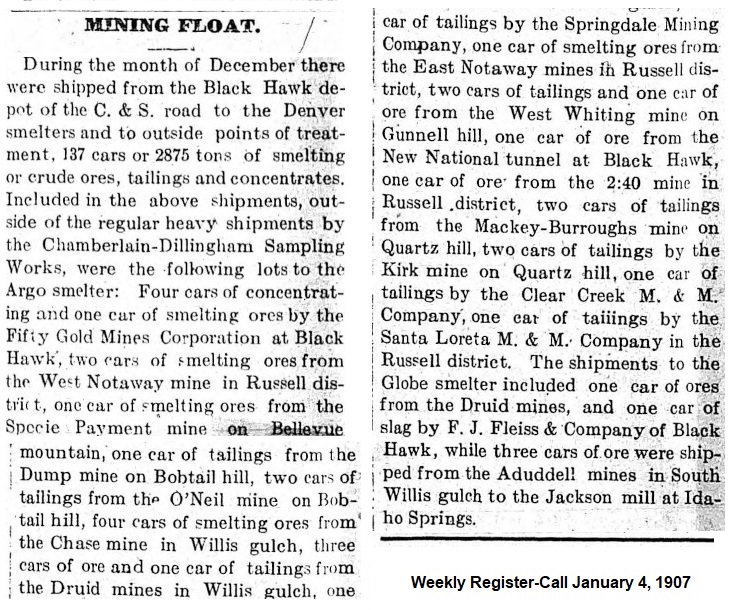

Continuing a detailed look at the Gilpin Tram's trackage and the mines served on Gunnell Hill, we'll continue where we last left off, at the Gunnell Mine. Next on the main line is the spur to the Grand Central mine.  M.P. 40.49 East Whiting Spur: This well-published photo is of the Grand Central Mine (or East Whiting), with the proud owners or promoters in front. The bridge is for the mine dump cars - they could dump into the Gilpin Tram spur below (the wide gauge?), or continue on to the waste rick dump. Note that when they painted the mine, they painted in a white trim board above the large doorway! Back on the main line, and almost directly across the spur track number 2 to the Gunnell Mine, a short spur veered off of the east side of the main line, serving the East Whiting Mine, more commonly known as the Grand Central Mine. The Grand Central was regular ore shipper on the Gilpin Tram, with surviving records of ore shipments being made in 1899 through 1904, 1906, and 1907. The “Daily Mining Investor” issue of September 11, 1905, gives a brief report: “S.T. Elliot, who has taken a lease and bond the Grand Central mine on Gunnell hill, starting preliminary work on the 15th inst., has succeeded in getting air through to the level to which the work will be pushed. Stoping has been started and Mr. Elliot is figuring on making the first shipment of ore on Monday or Tuesday of next week. When the mine is placed to proper condition between 15 and 20 men will be put to work. The Grand Central has not been worked for the past year and a half and at that time was operated by the Grand Central Company. According to reports a large quantity of very high grade ore was taken out, and at one time the property was considered one of the rich producers of the camp. Mr. Elliott, who will have charge of the mine, understands the business thoroughly, having acted as foreman of the Smuggler Union in Telluride, a period of ten years, until about two years ago.” Apparently, Mr. Elliott was successful, and was making ore shipments from the Grand Central Mine for at least 1906 and 1907. This mine could have shipped other years, but these are the only years for which I have seen written records of ore traffic. This is yet another example of how many mines in the region operate sporadically over the years, as investors and their money came and went. There are traffic records shwoing ore shipments on the tram in years 1899 to 1904, and 1906 to 1907. There could be more, it just means there are records existing for those particular periods. The Grand Central Mine is probably the best-known Gilpin County mine to model railroaders. This kit has been brought out by several kit manufacturers over the years, and in several scales. I think a kit is still available for this structure in HO, S and O from Trout Creek Engineering/Classic Miniatures. There seemed to be ongoing disagreements between the tramway and some of the local wagon teamsters. The Gilpin Observer reported on June 7, 1906, “Complaint was lodged against Wm. Gumma in the county court last week…he is being charged by the Tramway company with the destruction of property. The Tramway company alleged that defendant had removed a section of track crossing Prosser Street. Gumma claimed at the point in question the track was so highly-elevated as to obstruct wagon traffic and make it impossible to drive over it. He removed several fish plates and hitched his team to the track and made an opening wide enough for his team to pass through.” Well, that sure showed them!  A blurry enlargement of a photo shows the Grand Central mine with its prominent waste rock dump. The outhouse is conveniently perched on the waste dump. Note that the mine name is not painted on the walls in this view. This image is from the Denver Public Library, Western History collection.  This image is also from the Denver Public Library, Western History collection. It shows the Grand Central from a more distant vantage point, and the painted name can still be seen on the roof cupola. No outhouse is visible on the waste rock dump. This image was taken between 1901-1910.  Another blurry enlargement from yet another photo shows the east side of the Grand Central. This pastoral scene has cattle grazing nearby. This image is also from the Denver Public Library, Western History collection.  Today, nothing remains of the mine structure. The shaft is caved in, plugged, and only has a vent and USGS marker. The waste rock pile remains, and this is a view the site today, with Central City in the background. The mine waste rock dock visible at distant left center is the Freedom Mine site, which we looked at in previous posts.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Wood Mine.

|

This post was updated on .

I'd apparently stood atop that dump ....

unaware of its name....or exactly which I was on. unaware of its name....or exactly which I was on.      Makes one wonder if the middle man is McMaster and on the right is H.H.Barbee? DPL X-61799

UpSideDownC

in New Zealand |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Wood Mine.

|

In reply to this post by Keith Pashina

Chris, the gentleman on the right in your previous photo certainly looks like a mine owner! That could be a fun scene to model sometime - have some well dressed people standing in front of a mine, with an old-time photographer and camera out front.

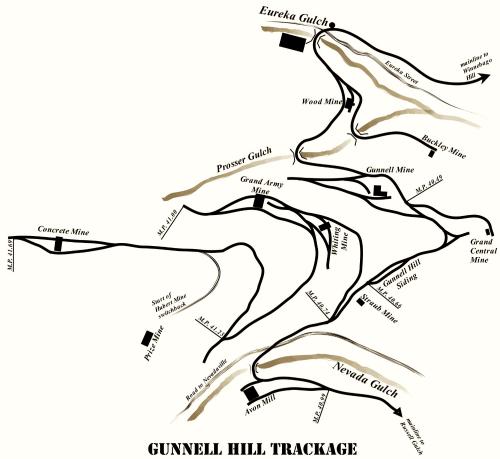

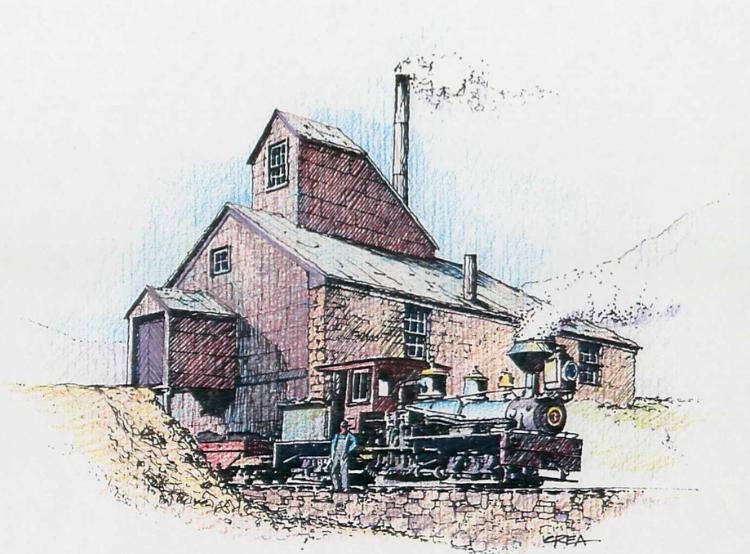

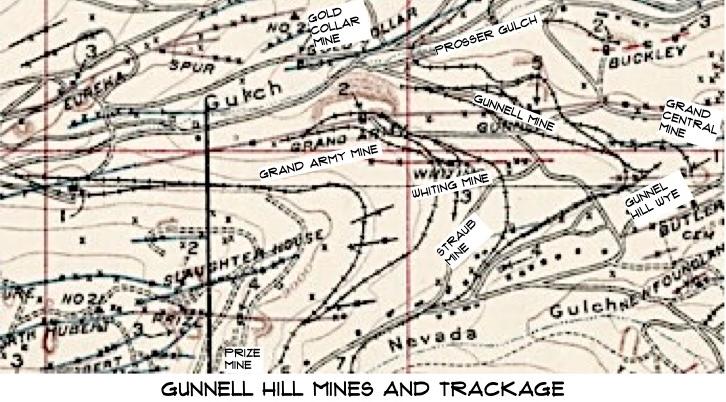

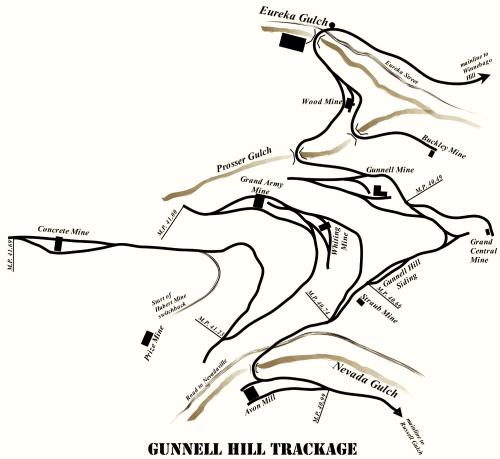

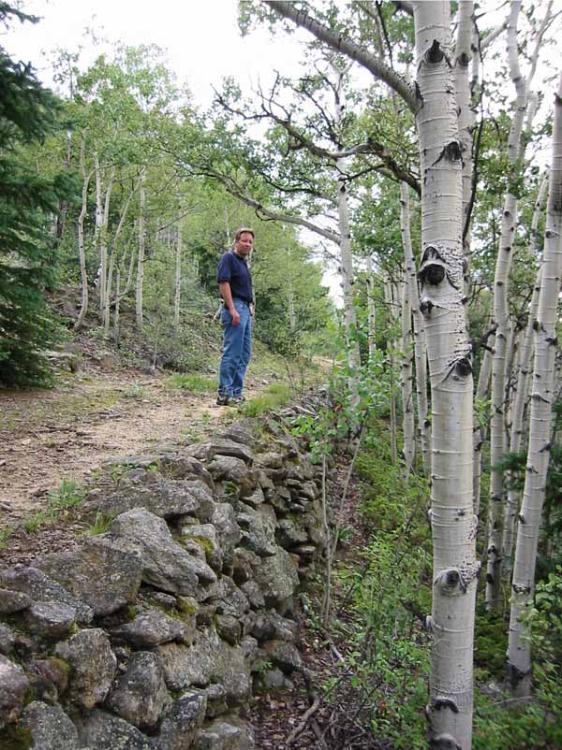

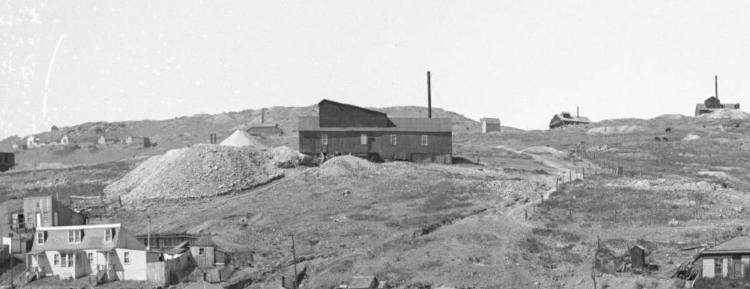

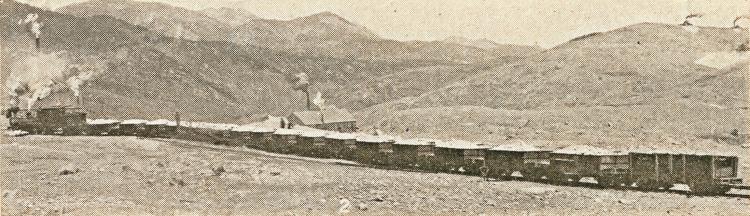

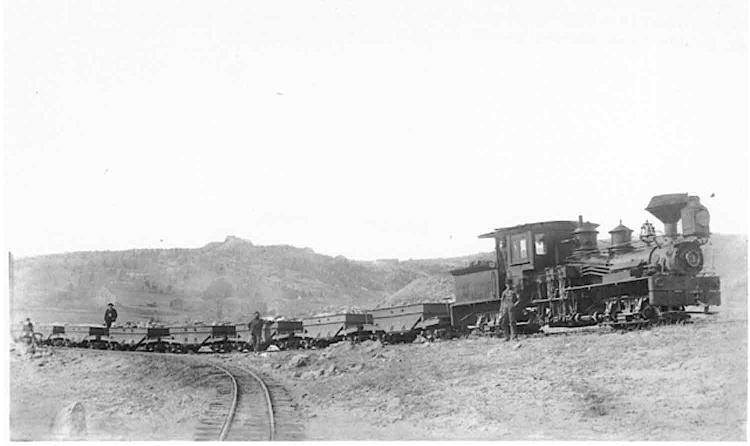

TRACKAGE ON GUNNEL HILL (continued)  Moving a short distance south on the mainline, the track continued to climb upgrade, and made curve to head west, now on the north slope of Gunnell Hill. At this point, the Gunnell Hill wye was constructed, one of three on the railroad. The mainline in this image curved to the left (we’re looking northeast) and the tail was the dirt road veering off to the right.  Standing on the main line looking northwest. The main curves from foreground to the left - the south leg of the Gunnell Hill wye is covered with aspen trees at right.  This image shows a train on Gunnell Hill siding, just a short distance west of the wye. A train of 16 loaded ore cars and an empty coal car are headed towards Black Hawk. M.P. 40.55 Gunnell Hill Wye: The Gunnell Hill wye was very compact, with the two legs of the wye of about 100’ radius. The site can be easily found today, and there are numerous cinders on the grade. The tail of the wye ended at a rocky outcrop located almost immediately above the East Whiting Mine. The two legs of the wye contained a total of 437 feet of trackage. I paced off the wye, and it is about 160' from the main line to the tail of the wye. The wye was also located on a sharp mainline curve and steep upgrade, where track wrapped around the brow of Gunnell Hill, and began heading more westerly towards Dogtown (Nevadaville). M.P. 40.63 Gunnell Hill Siding: On the south side of Gunnell Hill, there was a runaround track which was connected at both ends, and had a total of 331 feet of trackage – enough length for about 19 ore cars. This location can be found today, as a wide and fairly level spot with numerous cinders on the grade. This siding would have been convenient for assisting with car switching movements in the Gunnell Hill area. Interestingly, site reconnaissance shows that the Concrete Mine switchback seems to branch off at the middle of the siding, although the C&S mileage chart indicates the Concrete switchback branching off past the west end of this siding.  To help you get your bearings, here is the map of Gunnell Hill again. The Gunnell Hill wye and siding are at right center of this map.  An enlargement of a photo in “Glimpses of Golden Gilpin Colorado” is looking west at Gunnell Hill. I have labeled the mines in the photo to help understand the track arrangement in this area.  Not much remains today except traces of railroad grade.  Let’s step back a minute and look west at Gunnell Hill as it looks today. The big waste dump in center is the Gunnell Mine (you can see the structure at the left side) and above it, the Whiting Mine waste rock dump. The Gilpin Tram main line curved around the Gunnell dump, in the “notch” between piles on the right side of this photo.  The Whiting Mine was located on a lengthy spur diverging from the main line. An enlargement of a the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection photo shows the mine and an extensive waste rock dump. The stone retaining wall on the right side of the mine marks the location of the Gilpin Tram spur.  The Whiting Mine had stone walls on three side, and wood on the track side. The wood framed roof was clad with corrugated siding and had an unusual shape. This image is from the Mike Pyne collection. M.P. 40.93 Whiting Mine Spur: The Gilpin Tramway reached this mine by October 10, 1887, and this mine was regular shipper. The spur to this mine was 400 feet long. There are traffic records shwoing ore shipments on the tram in years 1901 to 1904, and 1906 to 1907, and 1914. There obviously are records missing, as noted by the 1887 report. It just means there are no records I have seen existing outside those particular years.  Joe Crea created this wonderful art of the Whiting Mine in its heyday.  The tramway spur to the Whiting Mine was supported on a lengthy stone retaining wall.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Wood Mine.

|

TRACKAGE ALONG GUNNELL HILL (continued)

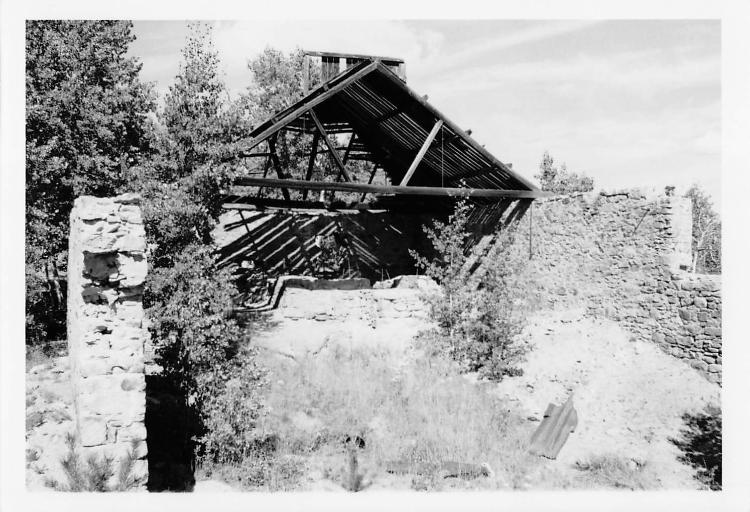

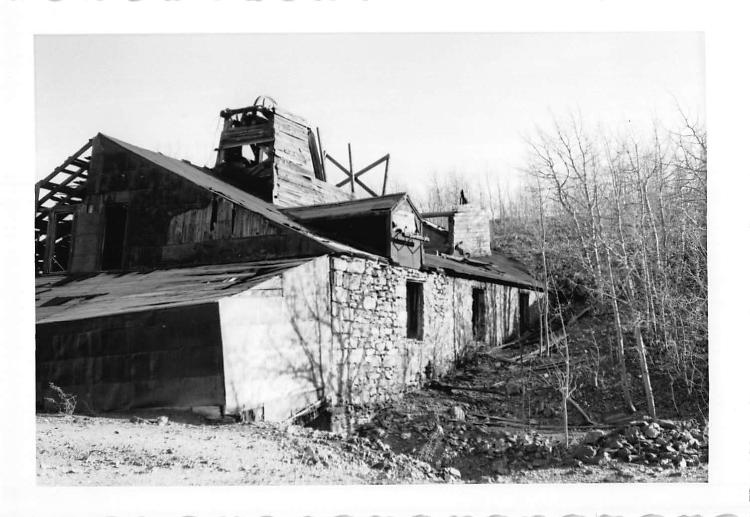

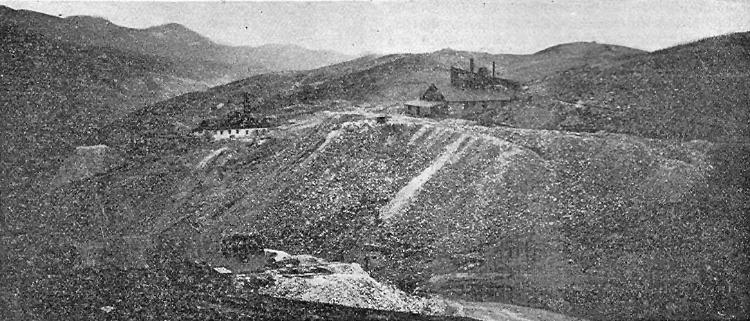

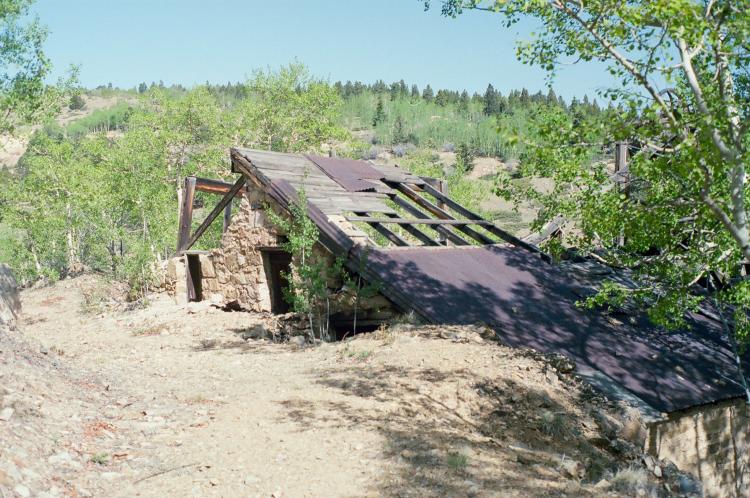

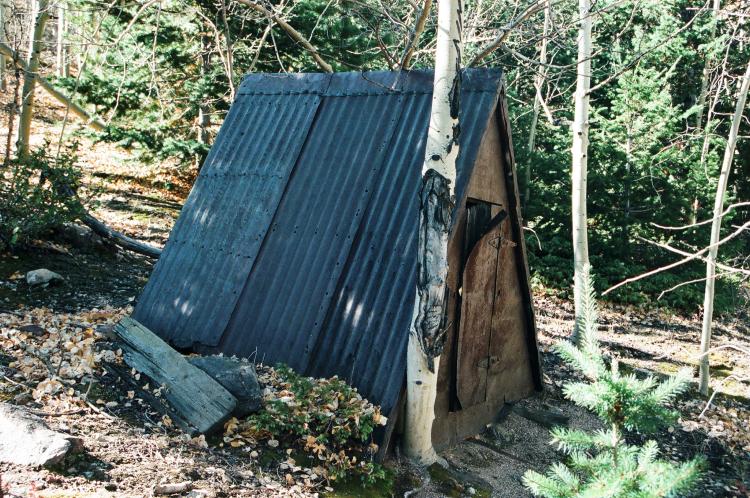

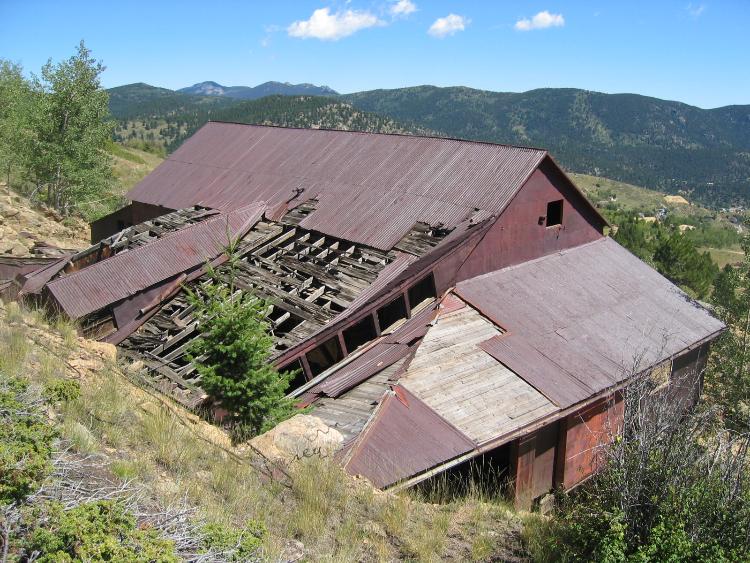

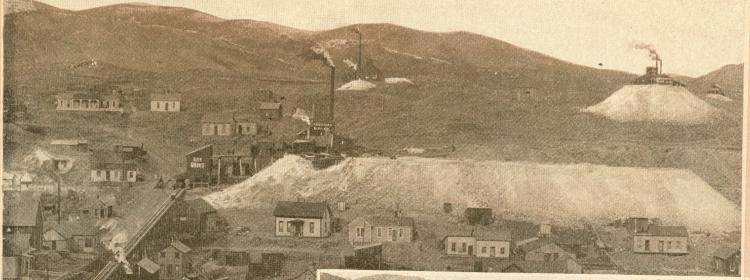

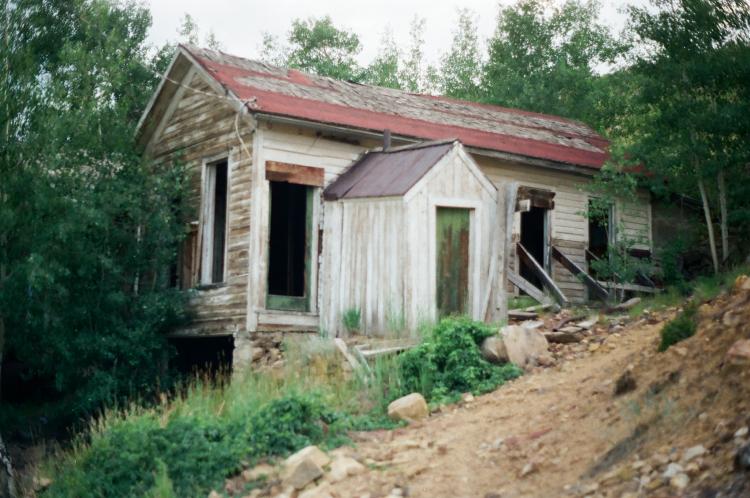

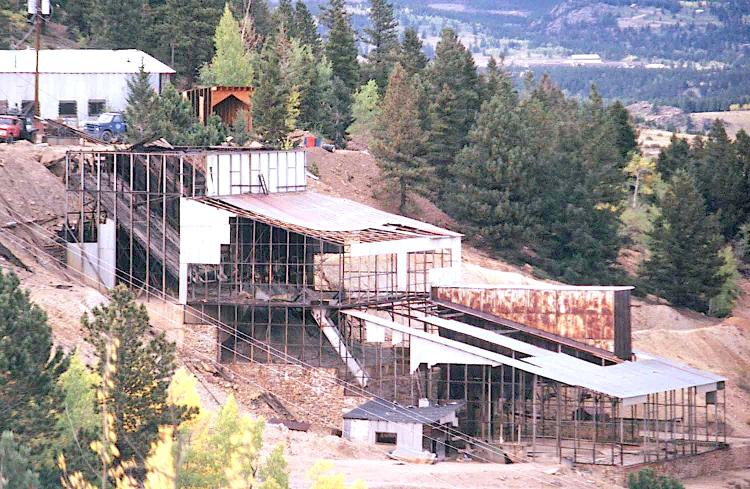

An enlargement of the USGS 1917 “Special” map shows some details of the mines and track on Gunnell Hill.  The Grand Army mine in its glory years. You can see the ore loading spur to the left of the mine, in front of the retaining wall. There is a grade above and behind the mine for coal unloading, and to feed the tail track for empties, which were then dropped by gravity under the mine loading (the lean-to on the right side of the building). An enlargement of a the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection. M.P. 41.00 Grand Army Mine Shafthouse: At the mine, the track ran beneath a covered ore loading track that dumped ore into cars from small side-loading bins. There were probably two tracks here, as the grade is relatively wide here, and study of old photos suggests there was a short spur here. Today the Grand Army Mine is derelict, but it is an impressive ruin. The rear and side walls are constructed of the typical Gilpin County style rubble stone, and are about 2’ thick. Much of the roof framing still stands, some still covered by corrugated metal roofing sheets. The first shipment of ore was from the Grand Army mine, on December 14, 1887, from the Grand Army shaft at the Gunnell to the Meade Mill of William Fullerton. The Grand Army Mine was operated jointly with the Gunnell Mine and Concrete Mines (after the Gunnell Mine owners prevailed in a lawsuit). I always wondered if they took ore out of all three shafts after that, or just one or two - I've never seen any records to confirm either way. There are paper records of this mine shipping on the Gilpin Tram from 1887 to 1904. In 1904, a pump house fire destroyed the pumps, and parts of the mine filled with water, halting operations. This shaft was 1,200-feet deep and operated as late as 1917. Although mining resumed in this mine in later years, the ore was hauled out through the Newhouse/Argo Tunnel, and this was after the Gilpin Tram was abandoned. About 25 years ago, the wooden enclosure over the ore loading track mostly collapsed – the top level likely contained a machine shop. Extensive wood cribbing lines both side of the ore loading track, and was needed to hold back the mountainside above, and the large waste rock dump on the downhill side.  The Grand Army mine in the 1960s or 1970s. The mine is in much better condition compared to today – the roof is still mostly in place, and the lean-to addition at front (which extended over the Gilpin Tram tracks for ore loading) is still standing. This image is from the Mike Pyne collection.  A view of the Grand Army Mine looking across Prosser Gulch, southward. This mine has an extensive waste rock dump. The Gunnell Mine can be seen near the left margin. Photo provided courtesy of the Mark Baldwin collection.  A colorful view of the Grand Army waste rock dump, from approximately the same viewpoint as in the previous photo.  Taken about 15 years ago, we see that most of the roof has collapsed, and the shed covering the ore loading tracks has collapsed. The wood debris is the collapsed remains of the ore loading shed, and is also partially washed in from the waste rock pile. A fair amount of the mine building stands today, thanks to the very sturdy stone walls and robust roof framing and headframe construction. In the photo, I can see Dan Abbott, Darel Leedy, Joe Crea and Lind Wickersham taking a break and discussing all things Gilpin -those were great days!  A view from the opposite (west) sideof the Grand Army mine. This photo taken about 1993, and the structure was in much better condition back then. Notice the magnficant stone work on the walls.  The Gilpin Tram loaded ore from small bins under a shed-like addition on the north side of the Grand Army mine.  On the south side of the Grand Army mine, we see how the rear of the shaft-house is built into the hillside. I am standing about on the upper Gilpin Tram spur grade. The tram pushed empty cars up this spur to a switchback, and then dropped by grade through the ore loading bins. Photo taken about 1993.  The Gilpin Tram also parked coal cars on the spur, and unloaded coal into the boilers below, through the large doorway opening in the stone wall.  A short, but safe distance from the Grand Army shaft house is this A-frame powder storage shed, used to store explosives.  This is an enlargement of Denver Public Library, Western History Collection Image L-237. In the background of this photo, the photographer captured the mines of Gunnell Hill. Although the image has a compressed, telephoto-like effect, it does illustrate how compact this mining district was. The Grand Central Mine is front center, with the Gunnell Mine immediately behind it.  Another great enlargement showing the Gunnell Hill mines grouped together. This is from Denver Public Library, Western History Collection Image L-68. The Grand CentraL Mine is again at front center, with the Grand Army to its upper left and the Whiting Mine further to the left. The Gunnell Mine is at right center, with its three smokestacks.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Wood Mine.

|

With apologies, I'm a little out of sequence with the following photos as they relate to Keith's Gilpin journey. Since I haven't posted before I thought I'd give it a try.

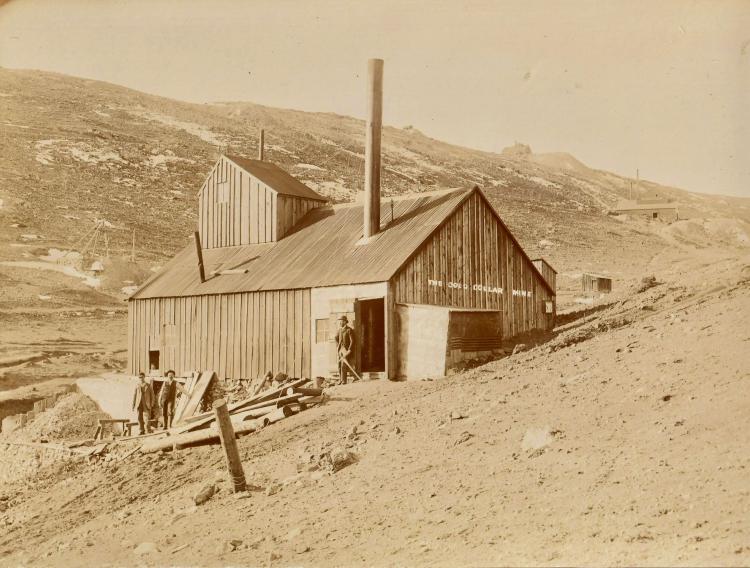

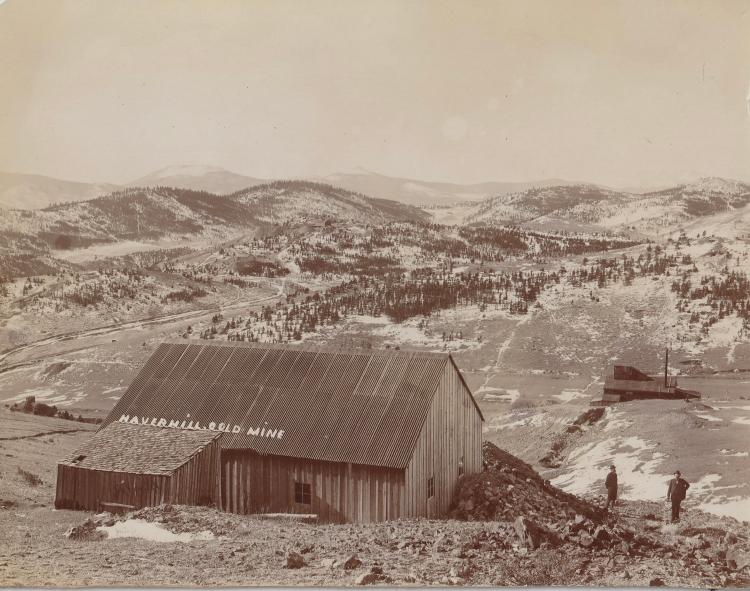

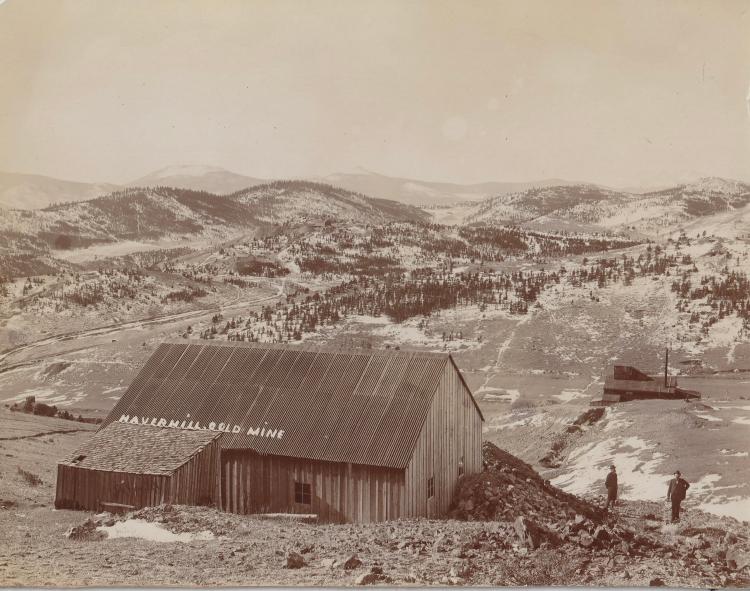

The first photo is another view of Prosser Gulch. The lower bridge across the gulch is the road bridge. The next bridge above that is the lower Gilpin Tram bridge on the Buckley Mine branch with a partial view of the Wood shaft house and three Gilpin tram cars on the siding. The mainline is the next bridge above that with Gold Collar Mine to the above right. Just to the left of the Gold Collar across the gulch is the Concrete mine. At the top left of the photo are the Gunnell and Whiting mines with a tram car below the Gunnell Mine waste rock trestle. The Grand Army shaft house with the large waste dump is to the right of those two mines with four tram cars on the tracks. Hope I got that correct.  I am not sure of the date on this photo but it must be an earlier photo of the Gold Collar mine with its board and batten siding. It doesn’t seem to have any of the additions that were added on later. The Concrete Mine is to the right further up the hill and you can barely see the lettering on the side of the mine. You can barely see the Gilpin Tram grade going across the top of the Gold Collar Mine as it travels to the end of track at the Concrete Mine. I’m not sure of what the mines on the ridge are. The mine at this size would make a great model.  Not sure where the Haverhill Mine was in relation to the other mines as I cannot find any reference to it on the internet, but it was in the batch with the previous two photos and the terrain appears to be from the same area. Maybe Keith can identify the mines in the distance and that would help with identification of the area. I see no Gilpin trackage.  An enlargement of the mines in the distance below.  I forgot I even had these photos and came across them yesterday. I was a follower of Keith's when he was on FreeRails so am glad to see the series revived. Kevin Fall |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Wood Mine.

|

Kevin,

Thank you for posting the four photos of Gilpin County - they are very interesting! The first photo you posted, the one of Prosser Gulch, is one of the very few photos showing track laid on the Gilpin Tram's Buckley Mine branch. On the right hand margin, you can also see 2 or more ore cars on the spur to the Woods Mine, also on the branch. The Gold Collar Mine is interesting, showing wooden board-and-batten siding. This would indeed make a very fine looking mine model. As to the last photos, showing the "Haverhill Gold Mine" and the enlarged background photo - I have no idea where this mine was located. I could not locate the photo perspective, when trying to align the background mountain profiles with the photo. Further, I could find no reference to any mine named Haverhill in my typical resources - School of Mines, Western History Collection, etc.. I wonder where this was taken? This photo shows a lot of interesting details of what appears to be a thriving mining area. My first thought was maybe upper Russell Gulch, but couldn't get it to align with any references that I have. Anyway, wonderful images! Yet another subject to be searching for further information on.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Haverhill Mine.

|

Been a little slow on this: excerpt from handwritten notes by me about 1994. Haverhill Mass. syndicate; Manager Newell, re-opened the Fisk in 1891. That's all I got, because back then I didn't write a lot down.

UpSideDownC

in New Zealand |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Haverhill Mine.

|

The Gunnell Hill Branches to the Mines - continued

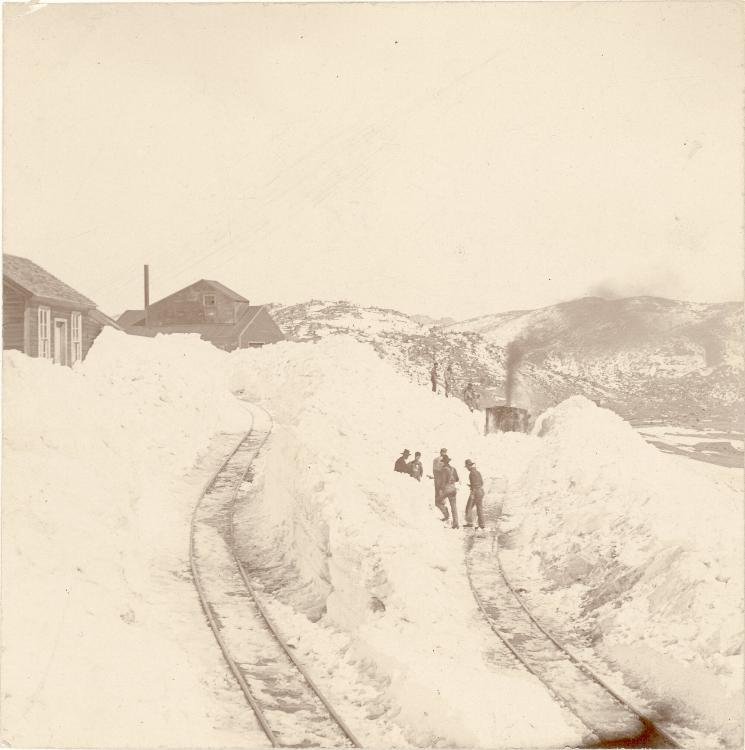

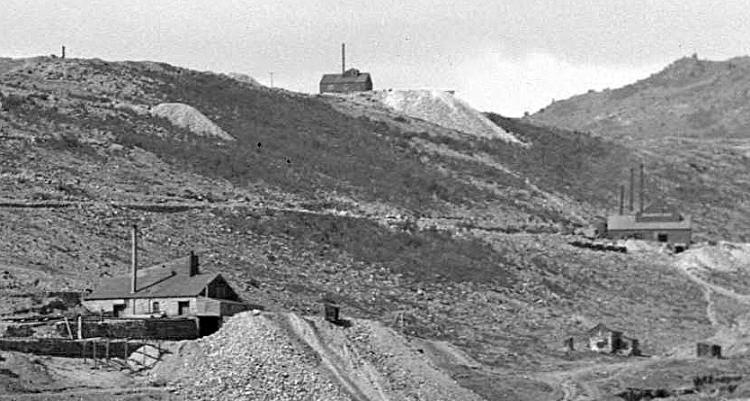

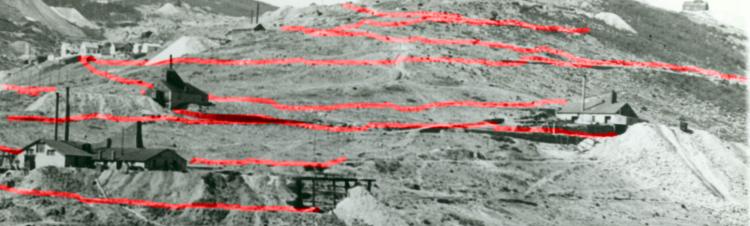

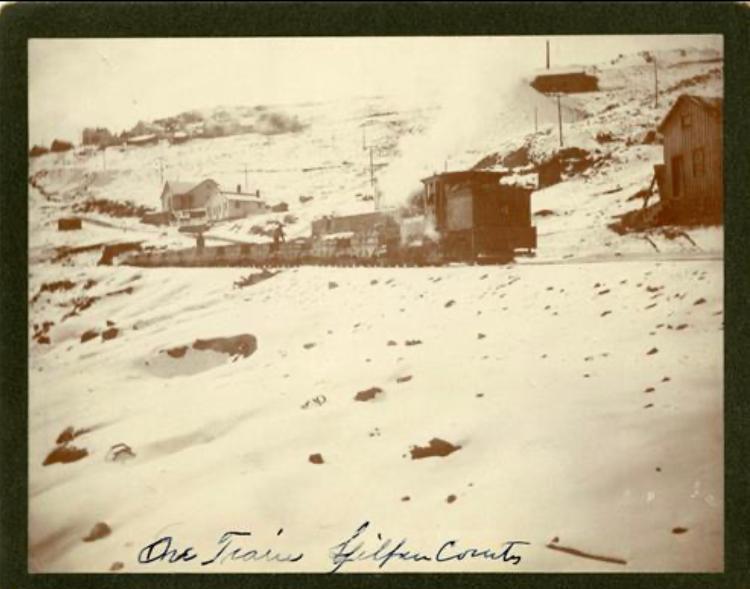

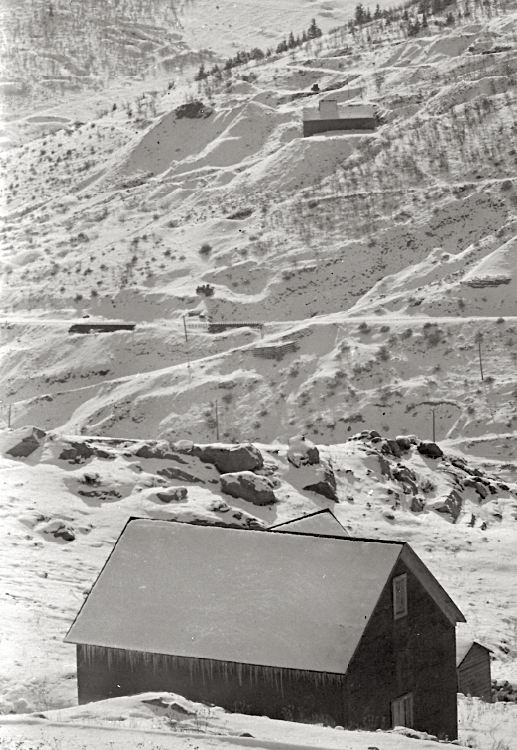

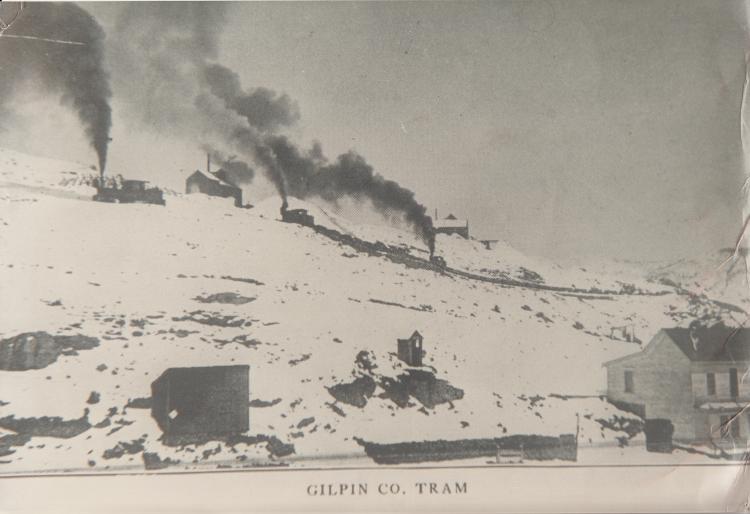

Continuing further up the Gunnell Hill spurs, we find Dan Abbott and Joe Crea exploring the gently-graded spur leading to the Concrete Mine. M.P. 40.74 Concrete Switchback: On the north side of the main line, the track began a steep climb on the first of several switchbacks to serve the Whiting, Grand Army, and Concrete mines, and eventually, the Hubert Mine. The Concrete Mine was a major producer. It not only operated its own shaft, but also the nearby Golden Treasure mine workings. Adjacent to the start of this series of switchback was the Straub Mine, which some records show was periodic tramway shipper. I have no record of a spur being laid directly to the shaft house. Getting back to the Concrete Mine, the Gilpin Observer newspaper reported on December 29, 1898, that, “…All ore ot small enough to pass through grizzlies after being hoisted to the surface is run through the crusher and conducted by means of a chute to tramway cars standing on a track which is enclosed by an L to the shaft building. Thence it is taken to the stamp mills at Blawk Haw, where it is dumped into an ore house and these passes to automatic ore feeders which are placed in front of stamp batteries.” This was an up-to-date operation, as most mines did not machine-crush ore at the mine, nor did all mills feed the stamp batteries with automatic feeders. This was a busy mine, too. The Gilpin Observer reported on May 4, 1899, that “…the Concrete Gold Mining company shipped over the Gilpin tramway to the Penn stamp mill in Black Hawk the past month, ending April 30, 180 cars or 1,500 tons of ore.” By 1902, ore shipments slowed down, the Gilpin Observer reporting on January 2, 1902, “the stamp mill ore output having averaged 25-30 tons per day…” In 1904, when the Gunnell Mine shaft house burned, the Concrete Mine miners had to temporarily halt work, the Gilpin Observer reporting that there was “too much gas from the fire” at that time. Operations seemed to slow down quickly – the Gilpin Observer reported on 6 miners working the mine on a lease at that time. There are traffic records showing ore shipments on the tram in years 1898 to 1903. There could be more, it just means there are records existing for those particular periods, and not for other years.  This image, from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, Image Z-3491, was taken in 1899 and has been published to show the difficulties in dealing with snow removal. It also shows what may be part of the Concrete mine in the background. Grand Army, Concrete and Hubert mines diverged from the main line. This image is looking northeast.  A companion photo, also taken by H.H. Lake, shows that now the track up the Whiting/Grand Army/Concrete/Hubert branch has been at least partially cleared. This photo also illustrates the abrupt change in grade, and curvy nature of the mine spurs. This image, also is from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, Image Z-3488.  An enlargement of a Denver Public Library, Western History Collection image L-230 shows a busy Concrete Mine, with at least 5 Gilpin Tram ore cars on the spur for ore loading.  Another photo from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, enlarged, shows the Concrete Mine at the center of this image. The Grand Army Mine is at left center, and the Gold Collar Mine at right Center.  This is from Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, taken in 1899, and shows the Grand Army Mine (lower left) and Concrete Mine at right center. The Gilpin Tram grade to the Concrete Mine can be clearly seen.  As with so many Gilpin Tram spurs, the spurs to the Concrete Mine and othes were supported on low dry-laid stone walls. Joe Crea is taking a break on the one leading to the Concrete Mine, and shows the general height of one of these walls.  I’m posting this map to orientate us to the network of trackage on Gunnell Hill again. The Concrete Mine is at the left edge of this map.  I overlaid red lines on this photo to denote where Gilpin Tram grade is visible in this photo. The main line passing the Gunnell Mine is the lowest level, at the bottom left corner. Above it are the Whiting and Grand Army mines, and above them, the switchbacks to the Concrete Mine. Even higher up Gunnell Hill is the branch to the Hubert Mine, which is where we’re headed next.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Haverhill Mine.

|

The Gunnell Hill Branches to the Mines - continued

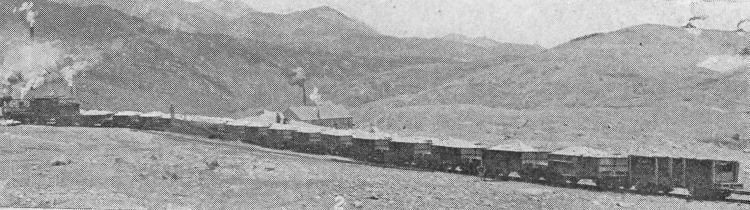

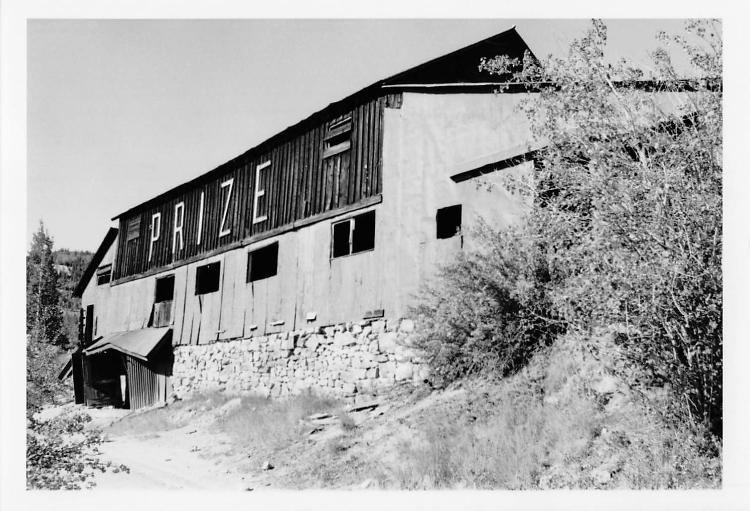

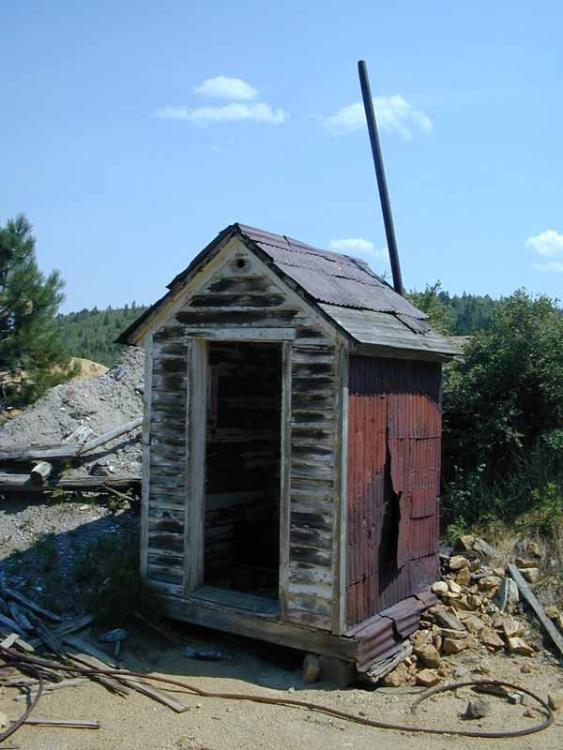

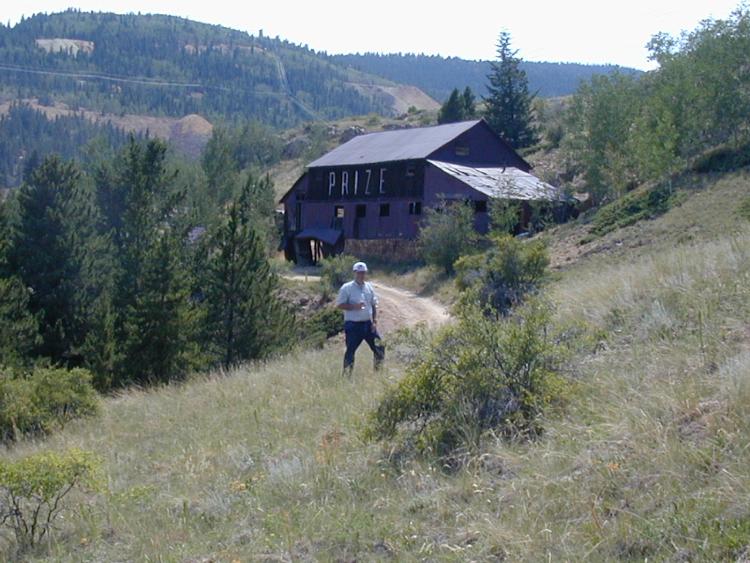

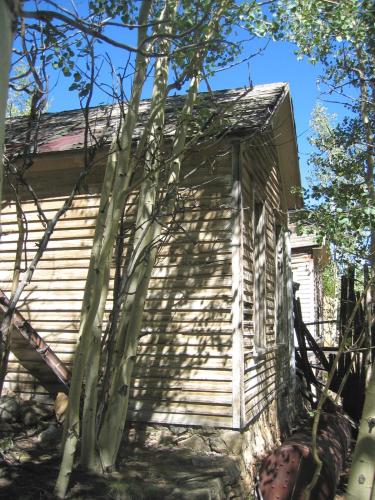

Here, C&Sng moderator Darel Leedy is checking out the first of several switchbacks to the Hubert Mine. The grade here, on the northeast slope of Gunnell Hill, is supported by a common dry-laid stone retaining wall.  Here is the Prize Mine, located near to, but not on the tail of one of the Gilpin Tram switchbacks. The mine dumps on the distant hillside are all on the north slope of Quartz Hill. There is still another section of this branch we haven’t explored yet - the Hubert Mine branch. Little is known about this branch - according to records, trackage was built to the Hubert Mine, a large ore producer on the north side of Nevadaville, close to and perched on the hillside above the town. For what years this mine shipped ore, how much, and when the branch was torn up seem to be sparsely documented. In May 1888, rails were extended to the Hubert Mine branch. This branch was described as branching off of the switchback from the Whiting Mine and working its way up to eventually reaching the Hubert Mine. The mine was managed by Henry C. Bolsinger, who not only was a prominent citizen and state senator, but was President of the Gilpin Tramway in 1886, and a Gilpin Tramway director in 1887 and 1888. The branch to the Hubert eventually required seven switchbacks. The first three, because they also served other mines, were documented in the Colorado & Southern mileage charts. These switchbacks also served the Whiting, Grand Army, and Concrete mines. We already stopped by M.P. 40.74 Concrete Switchback. M.P. 40.96 Concrete Switchback No. 2. The spur trackage at the Grand Army Mine was relatively congested, and the second switchback branched off almost right in front of the mine building. M.P. 41.23 Concrete Switchback No. 3: The tail track of this switchback was 236 feet long, and this switchback was located immediately southeast of the Prize Mine, graded on an open, grassy slope. The tail of this switchback is at about the same elevation as the wagon road that served the ore bins for the Prize Mine. There is no record that the Prize ever shipped on the Gilpin Tram, but perhaps the tail of the switchback was graded such that it could have been easily extended to the mine at a later date. I speculate that the Concrete Switchback No. 3 was built here to be a convenient location to extend a spur to the Prize Mine if ever needed. However, it appears the Prize Mine never became a shipper on the Gilpin Tram. The Weekly Register Call newspaper reported on October 14, 1887, “The Gilpin Tramway company have completed their switch track to the old bakery building of Andrew Bitzenhofer in east Nevadaville, out in their switch and are making good headway towards the Prize and Hubert mines.” A May 1888 newspaper report said the branch was being built to the Prize and Hubert Mines. Joseph W. Bostwick, who owned the Prize Mine, was also a Director of the Gilpin Tramway from 1900 to 1904. The Prize Mine also owned the adjacent Seuderberg Shaft, which was shown as being on a spur off of the Hubert Mine Branch. The Gilpin Observer reported on February 13, 1902, “…it (referring to the Prize Mine) has been idle for a number of years. It is supplied with a good plant of machinery, and connected by a siding with the main line of the Gilpin County Tramway.” So perhaps ore from the Prize Mine was shipped after all? Although I have never seen any paper records of this mine shipping on the tram, it is possible the ore was shipped out at the Seuderberg shaft, located on the top of Gunnell Hill and just north of Nevadaville. By 1914, this mine was connected to the Argo Tunnel, and ore was by then presumably shipped out to the mills in Idaho Springs.  This nice view of the Prize Mine is from the Mike Pyne collection, and perhaps takekn in the 1970s or 1980s. This mine shipped by ore wagon or truck, and there is no record it shipped on the Gilpin Tram.  A view of the southerly side of the Prize Mine, taken about 2000. The dirt road is at about the same elevation as a nearby tail of a switchback on the Gilpin Tram, and could have easily been graded as a spur if the need had ever arisen.  This is the southwesterly side of the Prize Mine, and shows how the mine was built into the hillside. The mine entrance seemed to be via a sloped adit, rather than a vertical shaft.  The powder house for the Prize Mine is this robust stone structure. Lane Stewart wrote a nice modeling article on this powder house in Gazette several years ago.  The Prize Mine also had this rather fancy outhouse nearby.  Intrepid Gilpin Tram historian Joe Crea is standing on the grade for the tail of one of the Gilpin Tram switchbacks leading to the Hubert Mine.  The next series of switchbacks continued to climb Gunnell Hill. Part of the grade was supported on a stone retaining wall just above the Prize Mine. This wall had been strengthened with metal tiebacks driven into the wall. The heads of each tieback shaft was scrap – look closely, and you’ll see old gears, bolts, bearings, etc. used. This would be an interesting detail to model!  The switchbacks continue to gain elevation, and are often supported on the typical dry-laid stone retaining walls. Here, Dan Abbott and Joe Crea are exploring the Gilpin Tram grade. We were looking for physical evidence of trackage, such as spikes or splice bars, but didn’t find any that day.  This photo is from “Glimpses of Golden Gilpin Colorado”, published about 1908, and shows the Hubert Mine (at the left end of the large waste rock dump). This was the end of the Hubert Mine spur. The homes nearby are all part of Nevadaville.  A contemporary photo looking at Nevadaville, shows the large waste rock dump for the Hubert Mine is still there. Continuing on, we finally reach the Hubert Mine. This sizeable mine acquired a mill in Nevadaville, named the Hubert Mill, and conveniently downhill from the mine. This was a 25 stamp mill that served the mine. Newspaper accounts describe the building of a Pickett Tramway, a bucket type tramway to deliver ore to the mill. Trackage seemed to be in place to the Hubert mine at least by 1892, as the Daily Register Call magazine reported, “Tuesday morning the mining reporter dropped in at the shaft building on the Hubert mine on Jones Mountain, Nevada district. Two of the miners who are working on company account in the 950 west level were busily engaged in loading stamp mill dirt into the tramway cars, which were shipped that afternoon to the Randolph stamp mill company in Black Hawk…” The Weekly Register Call newspaper reported on October 4, 1899, “…the ore crushed in Black Hawk is transported to the stamp mills over the Gilpin County tramway, racks and switches having been extended and put in at the mine. The shaft building is being covered with sheet iron, and other improvements added on the surface, that will expedite handling of the ore taken out during the stormy wintry months…” The Weekly Register Call newspaper reported on August 5, 1892,”Mr. J.V. Thompson, master mechanic of the Gilpin County Tramway company’s shop, on Monday was getting out the switch-bars and switches for a switch-back to the Concrete mine from the tramway line that extends to the Hubert mine.” So, this article is saying the Hubert Mine trackage was in place before the track was extended to the Concrete mine. Dan Abbott, in his book “The Gilpin Tram Era”, provides a newspaper account that describes the building of the aerial bucket tramway also states, “The ore in Black Hawk is transported to the stamp mills over the Gilpin Tramway. tracks and switches having been extended and put in at the Hubert Mine.” Finally, the newspaper account wraps up with, “The mine is connected to the stamp mills by two tramways, the company’s mill being supplied by a bucket tramway...and by the Gilpin Tramway, over which the smelting ore and stamp mill dirt is transported to Black Hawk.” By 1900, the first Hubert Mill had been replaced with a new, larger mill adjacent to the old building. The aerial bucket tramway was replaced with a 4-rail funicular railway (loaded car descends on one track while the empty car ascends on the other side). Perhaps with the enlarged milling capacities and new milling equipment the Gilpin Tramway was no longer needed, and this was the end of the branch. But, this is my speculation only. How long did trackage last to the mine? Well, there is this report in the Gilpin Observer on June 25, 1908, “The Gilpin tramway made connection with the Hubert this week and ore was being hauled this week.” That ends our look at Gunnell Hill and its network of trackage and busy mine traffic. Next, we’ll head up through Dogtown and the outskirts of Nevadaville.  Today, near the Hubert Mine location are these ruins. These may actually be a part of the Jones Shaft, a nearby operation.  Also near the Hubert Mine location are these remnants of ore loading bins – these served a road for wagon or truck traffic.  I am finishing up the look at Gunnell Hill with this pretty view, looking west, Gunnell Hill, with it’s prominent waste rock dumps is in the center rear. This view is looking up Eureka Gulch.  And, now we are back to where this current set of Gunnell Hill posts on this thread all started. This previously posted photo shows a Gilpin Tram train of loaded ore cars backing down the main line, on the north slope of Gunnell Hill. It will soon be passing the Straub Mine and coming to the Gunnell Hill siding. The Prize Mine is high up on the hill, at upper right.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway - The Haverhill Mine.

|

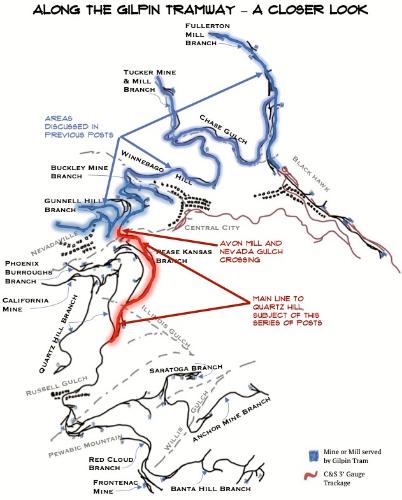

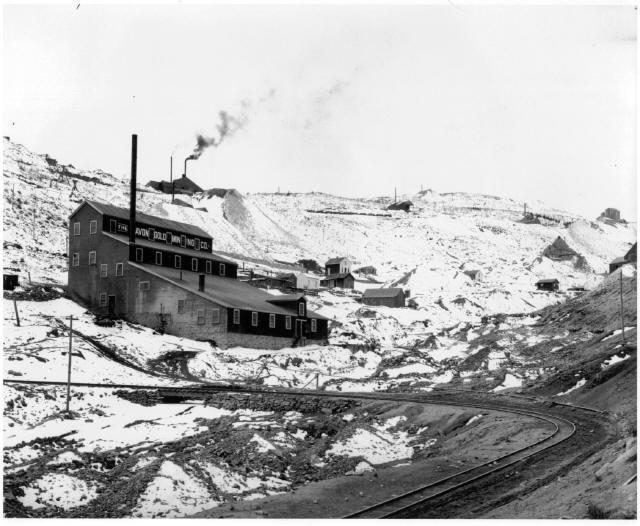

Along The Gilpin Tramway – A Closer Look (continued)

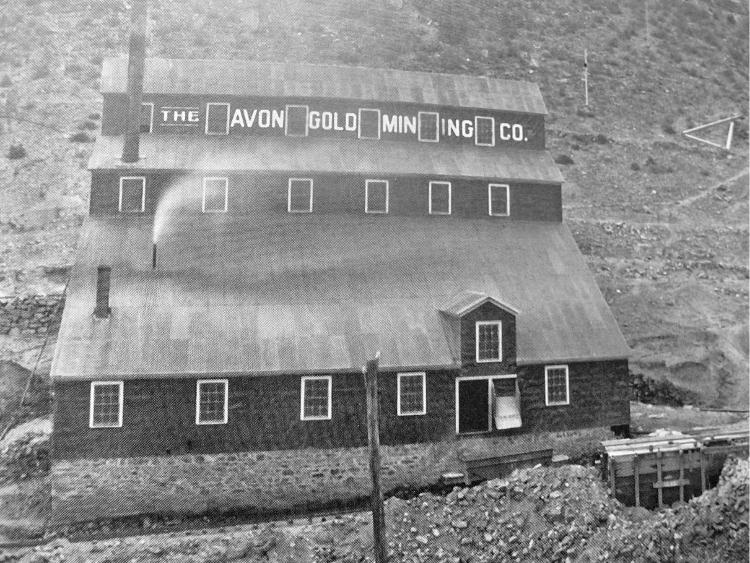

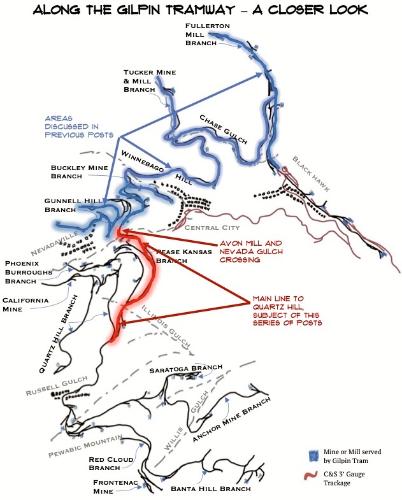

I’ll start with this image of a Gilpin Tramway document dated 1892. This was also the banner image on the first Gilpin Railroad Historical Society Newsletters, initiated, and mostly written by Dan Abbott. This marvelous set of newsletters eventually numbered 50 issues, and was and is, a fantastic compendium of information. It appears to me that all of the newsletter material was also included in Dan Abbott’s “The Gilpin Railroad Era” book published by Sundance Publications in 2009. If you are interested in reading about the Gilpin Tramway, this is THE BOOK to own.  This image is an enlargement of a photo showing Central City - that's the Schoolhouse (now known as the Coeur D'Alene) Mine in front. In the top left background are 4 or 5 homes, which are part of the Dogtown area. Note the Prize Mine to the immediate right of these homes.  The map above shows the part of the railroad discussed in this group of posts (in red) and areas covered in previous posts (in blue). In the last group of posts, we took a look at Gunnell Hill and its trackage in excruciating detail. This next post will look at the Gilpin Tramway mainline, as it continues generally west and southward to reach more mines on Quartz Hill, Russell Gulch, and beyond. Although Gunnell Hill was an important mining area, with extensive trackage built to serve the mines, even larger and more prosperous mining areas were located around Quartz Hill and Pewabic Mountain. We’ll be looking closely at these in upcoming posts. So, back on the south slope of Gunnell Hill, we continue west, looking ahead to Nevadaville and Quartz Hill. Shortly west of the Gunnell Hill siding, was the area known as “Dogtown”. I don’t know the origin of this name, but it’s colorful! Several residences were built on the hillside in this area, and 3 of them exist today, but in very poor shape. Dogtown was a part of Nevadaville, as that town granted right-of-way in 1886, the Gilpin Tram’s construction to cross Main Street “in Dogtown”. On February 6 1891, the Dogtown location attained some notoriety when Nevadaville fireman were roused after several residents called the alarm, as one of the homes appeared to be on fire. Rushing to the scene, it was found a Gilpin Tram ore car had derailed, and the stopped train’s headlight was shining on the side of a house, the glow giving the appearance of the fire! Embarrassed, the Nevadaville firefighters helped the Gilpin Tram crew re-rail the car, and both the train and firefighters went on their way.  One of the remaining Dogtown residences remaining. This photo was taken in 1993, so the building is in much worse condition today!  A view of the remaining 3 buildings in Dogtown.  There are several dry-laid retaining walls remaining in the town. The street would have been at the bottom of the wall, and on the top, the long-gone homes and small yards. There were a lot of people living here at one time.  This photo shows Quartz Hill on the left (the taller hill). The large mine dumps were served by the Gilpin Tram – there were three levels of track here. On the right are the Gunnell and Whiting Mines on Gunnell Hill. Part of Dogtown can be seen at center, and Nevadaville is out of sight further up the gulch. This image is from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, image L-51. Back at Gunnell Hill, in our previous posts, we temporarily halted at about where the Gunnell Hill siding was located. This siding was at Milepost 40.63. Just 20’ west of the west switch, as milepost 40.74, was the turnout for the connection to the Concrete Mine and Hubert Mine branches. The main line continued climbing upgrade through Nevada Gulch, then made a sharp turn south as it crossed the gulch, and began its climb along the eastern and southern slopes of Quartz Hill. The grade here, to Leavenworth Siding, was about 3%.  A loaded Gilpin Tram ore train is at Gunnell Hill siding, near where the branch to the Hubert and Concrete Mines veered off, and downslope of the Prize Mine. This is where our tour of the mainline left off in prior posts. There is an empty coal car tacked on the rear of the train, and no caboose. The image came from the “Glimpses of Golden Gilpin” promotional booklet published about 1908.  Nevada Gulch was crossed on this small bridge, typical of Gilpin Tram construction. It appears the channel under the bridge is partly silted in from runoff down the gulch, which was filled with numerous mines. This is an enlargement of a photo from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.  This bridge location is where the Gilpin Tram crossed Nevada Gulch. It made a broad, almost half circle turn across the gulch (view is looking east, towards Central City). Although this bridges was on the site of the railroad bridge, I think these remains are from a vehicle bridge built post-abandonment. This bridge is gone today, having been replaced with a culvert and riprap as part of a drainage control project. The Avon Mill The Avon Mill was directly served by two spurs off of the Gilpin Tram, located on the south side of the Nevada Gulch crossing. The lower spur was at milepost 40.92 and the upper spur at milepost 40.99. The Avon Mill was owned, at least for a short time, by the same ownership of the Climax Mine, which is at the top of Quartz Hill. We will look at this operation in detail in a future post, but there are several interesting details about this mill. The reports from “The Economic Geology of Gilpin County,” published in 1917, report that the Avon Mill was used for processing ore that was not high grade enough to be sent directly to the smelter. It reported the mill (in 1916) had 30 rapid-drop stamps (not the slow-drop Gilpin County type typically used), 6 Gilpin County bumping tables, and 1 Wilfley table. The mill was able to attain a 10:1 concentration with this equipment. The average value of the concentrated ore was $20 per ton; most of the precious metals were recovered on the amalgamating plates on the stamps and concentrating tables. I have seen a Gilpin Tram report showing 2 cars of concentrates being shipped to the Tucker Mill for further processing. I never have seen where else the concentrates might have been shipped - maybe to the Sampling Works or other mill in Black Hawk. The owners built an aerial tramway between mine and mill. This 3,700 foot long tramway was one of only two I am aware of being built in Gilpin County (the other was between the Colorado-Carr Mine and Randolph Mill). This tramway used the “Hallidie endless wire rope” system, which, if I understand correctly, relied on continuous operation of the buckets (not latched and unlatched at the terminals like other systems). The system also used the weight of descending buckets to pull up the empty returning buckets. Either the aerial tramway or the Climax Mine operation apparently were not too successful. The aerial tramway built in 1900, and this may have coincided with the construction of the mill, too. Shortly after put in operation, the Gilpin County Observer reported on September 26, 1902, “…The aerial tramway from the company’s Climax mine to the mill at the foot of Quartz Hill, for some reason, does not do its work as was anticipated…” A report in the Gilpin County Observer on October 8, 1903, stated, “Workmen have been busily engaged this week tearing down the aerial tram from the Avon mine to the mill.” I speculate that the Climax Mine was not the producer that the operators expected, as a report in the Weekly Register-Call newspaper on October 9, 1903 The Gilpin Tram built two spurs to the mill; a lower spur for loading out mill concentrates, to be shipped elsewhere for further processing and on the uphill side of the mill, a second short spur for coal unloading. Alongside the main line track between the mill and Gunnell Mine, a pipeline was laid for the water supply for the mill. Water pumped from the Gunnell Mine was the source of this water. You can see this pipe in the photo below. The Gilpin County Observer reported a fire at the Gunnell Mine on March 14, 1904, and noted,” The Avon Mill has also been forced to close for lack of water.” This was a huge problem for the mill – when the Gunnell Mine burned, the water source to the mill literally dried up, and operations ceased until the mine (and water source) were rebuilt. The mill was shut down for at least 6 years thereafter. The Gilpin Observer newspaper reported on March 24, 1910, that a new lessee was planning on reopening the mill, which “the Avon Mill has been idle for six years. It has last been operated when the Gunnell Mine was being worked. When the shaft buildings and machinery were destroyed by fire on the Gunnell and the mine ceased to work, the Avon Mill was forced to shut down as the water used in the mill was pumped from the Gunnell and piped to the mill.” The “C&S Official Mileage” book dated July 1, 1914, lists the two spurs in place to the Avon Mill. “The Economic Geology of Gilpin County,” published in 1917, described the mill equipment in place in 1916.  The Avon Mill was located near the bridge crossing over Nevada Gulch. The Gilpin Tram main line made a sharp curve here. Quartz Hill and many of its mines are visible behind the mill. Note the water pipe laid alongside the track, which delivered water to the mill from the Gunnell Mine. Photo from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.  The lettering styles in use on buildings are interesting, and if modeled, add some character to the model. Periods at the end of the name were common during this period.  Another enlargement of the previous image, from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, image L-310. The mill was supported on a sturdy stone foundation. The mill followed what I think of as the classic mill configuration, using the slope of the hill and gravity to facilitate ore handling. Parts of lower Nevadaville are visible on the right. The mine above the mill was the Phoenix-Burroughs Mine, served by the Gilpin Tram.  This image was published in the “Gilpin Tram Era” by Sundance Publications, and shows the north side of the mill. The lower tramway spur ran alongside the mill, and a metal chute for concentrate loading is visible in the double door . An ore car is parked beneath the loading chute. I wonder what the wooden stucture at right edge was for – maybe a water cistern?  Enlargement of the previous Denver Public Library photo shows a portion of the Hallidie aerial tramway that ran from the Climax Mine down to the mill. The bin-like structure is the ore loading point at the mine. We’ll see more of this later, when we head up the Quartz Hill branch.  Enlargement of another image from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection shows a view of the east side. There is a trestle leading into the top of the mill. To me, this does not look like it was a lower aerial tramway terminus, so perhaps this image was taken after 1903, when the aerial tramway was dismantled.  Nothing remains of the Avon mill today, except some of the stone foundations.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

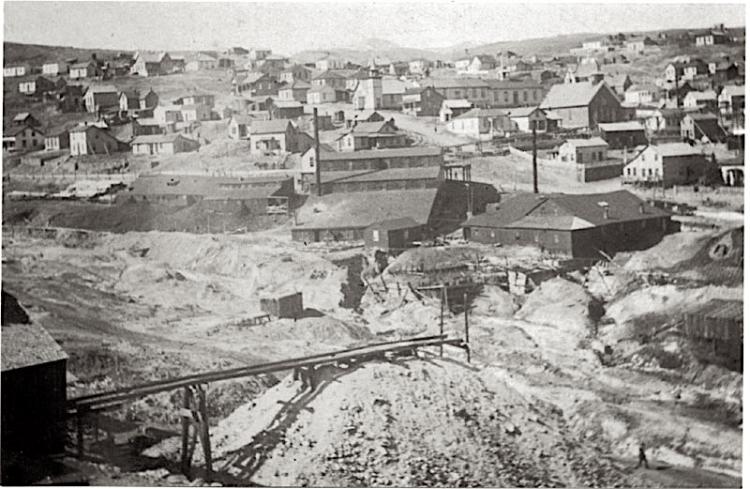

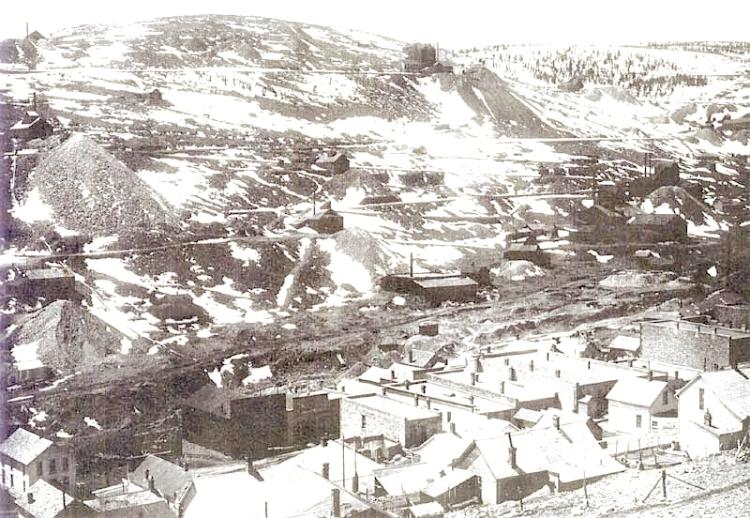

Nevadaville also had several stamp mills at one time (only two, the Gold Coin and Avon Mills were served directly by the Gilpin Tram). The mill in the center of this image was the Hubert Mill, which was served by its own dedicated aerial tram, and later a funicular tram. The mill's development may have coincided with the demise of the Gilpin Tram's Hubert Branch. This image is from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection. Nevadaville Nevadaville predates the Gilpin Tram era. First settled about 1859, it was originally named Nevada City, but the U. S. Post Office thought the mail might get mixed up with Nevada City, California, so the USPS changed the name to Bald Mountain (a nearby mountain, a few miles west of town). The residents didn’t like the name change, and referred to it as Nevadaville. A real gold boom town, Nevadavile was at first bigger than Denver, and was nearly the same size as Central City, but only for a while. Nevadaville was and is not favored by readily available water supply, so the town eventually capped out at about 6,000 population. The town grew and bust, depending on the mining activity. There was a lot activity in the 1870s and 1880s, then a decline, and regrowth in the late 1890s when many of the deeper mines on nearby Quartz Hill were developed. Even though Nevadaville was a pretty sizeable community, the Gilpin Tram did not serve it directly - the railroad was built to haul ore, not passengers. Mine spurs were all over Quartz Hill, on the south side of the town, and we previously looked at the Hubert Mine branch, high above on the north side of town. But, the tram never had a depot nor trackage in the town itself. Most of Nevadaville’s structures are long gone, but there are still several interesting remaining buildings, and a few people still live here. If you ever visit the area, Nevadaville is about 1 mile up a well graded dirt road from Central City.  Above, another view of Nevadaville looking towards Quartz Hill. Most of the structures visible in the photo have not survived to today. Don't worry though, there are still several interesting structures and remains left to explore, and we'll see some of them next.  A contemporary view from about the same vantage point at the previous photo. Most of Nevadaville has disappeared! The shaft in the foreground is the Jones Mine shaft on Gunnell Hill.  This little stone house is along the road between Central City and Nevadaville.  Looking up Nevadaville’s Main Street circa 1925. There are many commercial buildings still standing, but no humabn activity visible. Nevadaville was well on its way to ghost town status at this time. This image is from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.  A contemporary view about the same vantage point. Most buildings have long been torn down.  The former City Hall/Jail is a really interesting structure. The building is set onto a steep hillside on a rubble stone foundation. According the book, “Up the Gulch, A Walking Tour Guide of Black Hawk, Central City and Nevadaville”, the City Hall was constructed in 1872 as a residence, and converted to City Hall in 1883. Missing today, it used to have a bell tower for the volunteer fire department housed inside. The lower level housed the city jail. The upper floor was for city offices and a courtroom.  The backside of the City Hall is just as interesting. Note the stone foundation and door leading to the jail. The siding is very aged, and this would make a wonderful model. The buidling is privately owned, and the present owners have done a substantial amount of restoration since this photo was taken.  We are looking south over "Main Street" at Quartz Hill. A few structures in town remain, and there are many stone foundations remaining where structures have been torn down. The building across the street was the Bon Ton Saloon, one of 13 saloons in Nevadaville at one time.  The former Masonic Lodge building has been kept in good condition over the years. According the book, “Up the Gulch, A Walking Tour Guide of Black Hawk, Central City and Nevadaville”, this building was built in 1879. Each July, the Masons hold a pancake breakfast in the building to fund their restoration work.  The Pozo Mine is easily seen on the south side of the road, on the western edge of town. Note the remaining Nevadaville buildings in the background. This structure has been preserved, and appears to be in decent condition.  The backside, or south side of the buidling may less known to visitors. This mine was not served directly by the Gilpin Tram. In fact, the closest any track got to it was about halfway up the Quartz Hill mountainside. This building was immortalized as a kit by Link and Pin Hobbies about 35 years ago.  This is the Pozo Mine hoist house, located on the south side of the shaft house.  Looking inside the Pozo Mine shafthouse, we get a good view of the framing used to construct the building.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

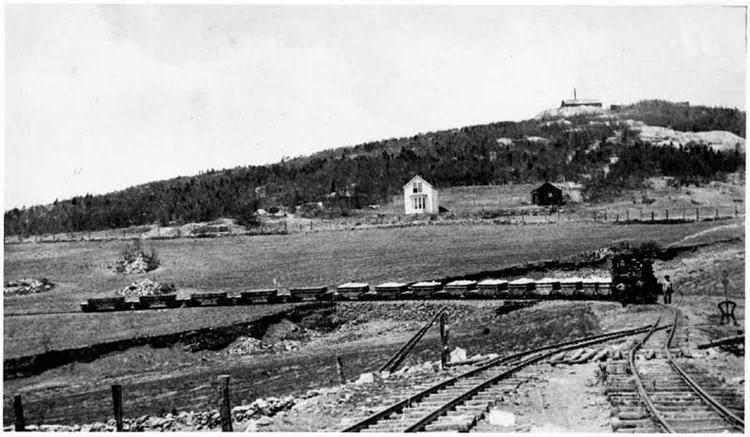

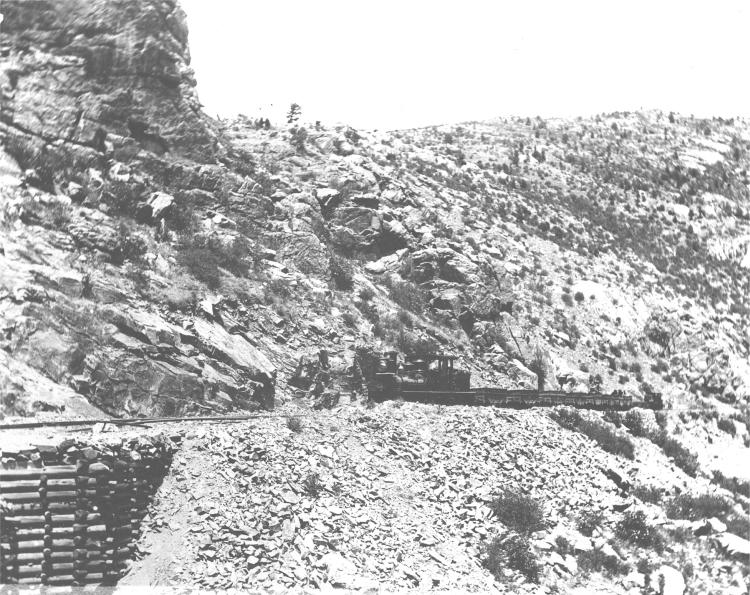

This is a good time to review the route that we are taking in this post. The red line shows the mainline area covered. The Gilpin Tram Main Line Along Quartz Hill Continuing on from the Avon Mill, the mainline continues about a 3% climb along the east slope of Quartz Hill. The grading is cut into the hillside here. Perhaps 300 or 400 feet upgrade, we come to the site of the Columbia Mine. The Columbia Mine shipped ore on the Gilpin Tram, and eventually had spur here for ore unlodaing. The Gilpin Observer reported on May 30, 1902, that “Regular shipments of ore are being made to Black Hawk from the Columbia Mine on Quartz Hill.” The mine was prospering, for the Gilpin Observer newspaper reported on June 20, 1902, that “Superintendent and General Manager Fred Kruse has put in a switch track from the main line of the Gilpin Tramway Company to the Columbia mine on Quartz Hill. Heretofore the ore from that company has been loaded into tramway cars standing on the main track. There is considerable crude ore being shipped from this mine over the tramway.” Perhaps some motivation to lay in a spur was the risk of accidents. The Gilpin Observer reported on June 13, 1901 a mishap: “Thursday night a loaded tramway car standing on the main track below and alongside the main dump of the Columbia Mine on Quartz Hill started down the track for some unknown reason. By the time it reached the curve just before the tramway bridge crossing of Nevada gulch it had gained great velocity and at the bridge crossing it jumped the track and lodged in the gulch below.” I am not certain exactly where the spur was laid, but assume it was near where the waste rock dump is today. We soon encounter the branch switch to the Pease-Kansas Branch, at milepost 41.41, or about 400 feet from the Avon Mill. This was a very busy branch in its day, but we’ll come back later to take a closer look at the mines there. As we continue southward along the grade, we pass the remains of an ore processing mill on the east side of the grade. This was an operation that was built long after the Gilpin Tram was torn up. I always wonderd if this was connected to mining operations on top of Quartz Hill, in the later Glory Hole operations (more on that in future posts), but never could find any documentation on it. It’s an interesting ruin of the building shell and some old dump trucks.  In this photo, I was standing up near the top of Gunnell Hill, looking southward. The red arrow points to the Gilpin Tram’s main line, which was graded into a substantial dirt road sometime after the railroad was torn up. The mainline very gradually climbed around the east nose of Quartz Hill, where two of the mine branches climbed at a much steeper grade to reach the mines.  Here, I'm standing on the Pease-Kansas Branch grade. The dirt road along the east margin is the former mainline. The branch grade is still readily visible, more of a well-used footpath than a road. There is a significant height difference between the branch and mainline.  The arrow points to Columbia Mine, located near the Gilpin Tram mainline. The mainline is the track on the right, and the trackage on the left side is part of the Pease-Kansas branch. This is an enleagement of part of the USGS 1917 Special map.  This enlarged image, from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, ,shows the northeast side of Quartz Hill. The Gilpin Tram main line can be seen as the horizontal grade mid-height in this photo.  This image was taken by H.H. Lake, and is identified as the Gilpin Tram trackage on the east side of Quartz Hill near the Columbia Mine dump. This image came from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection (DPL).  An enlargement of the previous DPL photo probably shows the Columbia Mine. There are two mine shafthouses shown – I don’t know which one is the Columbia – the area is very eroded and partly churned up by mining activity post-railroad abandonment, and I have never figured this out!  Another enlargement of the same DPL shows this detail on the main line. This is a substantial wooden retaining wall with a wooden culvert at the top. Lso, note the utily line poles extending up the hillside. Several mines were “modern” at this time, and these poles carry either telephone or electric piwer. This site is easily found today, due to the substantial erosion from water runoff that has ensued over the years. Nothing remains of this retaining wall today.  A companion image taken by H.H. Lake, possibly taken the same day as the previous photo, and it shows Gilpin Tram trackage on the east side of Quartz Hill. This image came from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection (DPL). I wonder if this is H.H. Lake’s son in the photo?  Another H.H. Lake photo, also taken on the main line on the east side of Quartz Hill. The seated gentleman may be H.H. Lake himself.  As you walk around the road that is the former Gilpin Tram mainline, you encounter these mill remains near the southeast corner of Quartz Hill. The main line grade is hidden in the trees behind and slightly above the top of the mill. This mill post-dates the Gilpin, and I do not know much about it. I am guessing it was built in the 1930s or later. Continuing south, we come to location of where the Phoenix-Burroughs Branch verged off of the main line, at Milepost 41.85. We will come back to this location in a future post and look at the mining operations there. Rounding the east end of Quartz Hill, we are now heading westward, towards Russell Gulch. Soon, we come to the site of the spur that split off of the south side of the track, and led to the Gettysburg Mine, at Milepost 42.13. This spur further diverged into two short spurs. I could not learn much about this mine, and have no information on the years it operated, how much it shipped, nor what it looked like. Today, all that remains is the waste rock dump and some stone and brick debris. The owner of this mine was R.L. Martin. If the name sounds familiar, it’s because he owned and operated the Wheeler Mill, and built trackage to it off of the Fullerton Mill Branch. R.L. Martin was a prominent local miner, and his name pops up associated with several local mine properties. Just a short distance further west, is the junction to the Quartz Hill Branch at Milepost 42.13, which split off of the main line headed east, and immediately encountering a stiff uphill grade. There was a lot of activity and history on this branch, and I will discuss that in another future post. Adjacent to the Quartz Hill Branch connection was Leavenworth Siding, an important runaround track located at Milepost 42.16. At the west end of the runaround track was a cattle guard. A photo shows the only cattle guard I have seen photographed on the Gilpin Tram. I wonder how common they were? At this point, I will end this post. The next one will look at the mines and views along the Pease-Kansas Branch.  On the south side of Quartz Hill, we come to Leavenworth Siding. This siding would have been handy for doing runarounds of cars, and getting some switching done before the steep climbs up the mine branches. This wonderful old photo shows I think Shay #3 pulling 10 or more loads and 5 empty cars eastward, towards Black Hawk. Note the other details here - a harp stand at the mainline turnout, the cattle guard (at the double track portion just this side of the harp switch stand) and fenced-in right-of-way. Of course, this view is all overgrown with trees today. This photo is provided courtesy of the Mark Baldwin collection.  A contemporary view of Leavenworth siding. I am standing downhill from the grade, and a low dry stacked stone retaining wall above marks the track location. The grade here is about 20’ south of the Central City-Russell Gulch road.  Shay #3 is starting to ascend the Quartz Hill Mine branch with a load of empty cars. The mainline to Black Hawk is the track in the foreground. Not the harp switch stand (left margin) for the mine branch. Leavenworth siding was behind the last car in this train. This photo is provided courtesy of the Mark Baldwin collection.  Another photo, courtesy of from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection (DPL), shows Shay #3 at Leavenworth siding, taken during scrapping operations in 1917. The crew is facing the camera between the siding tracks, and several mines on top of Quartz Hill are visible in the background. At this point, I will end this post. The next one will look at the mines and views along the Pease-Kansas Branch.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

|

Thanks Keith! Always a wealth of information!!

Tony Kassin |

|

Keith, the Gilpin has always been a fascination.

Do you know how trains were dispatched? Would they run and work a particular segment of the line on a given day, or would the train work the whole railroad? With all the switchbacks, how did crews remember what was what and where? I infer that places like Leavenworth siding would be a place to stage trains, that is to collect loads for various mines, or set out empties while you worked different areas?

Keith Hayes

Leadville in Sn3 |

|

Keith, good questions on how Gilpin Tram trains were dispatched. There's not a lot of information available, so like so many things about the tram, it's speculation and a best guess!

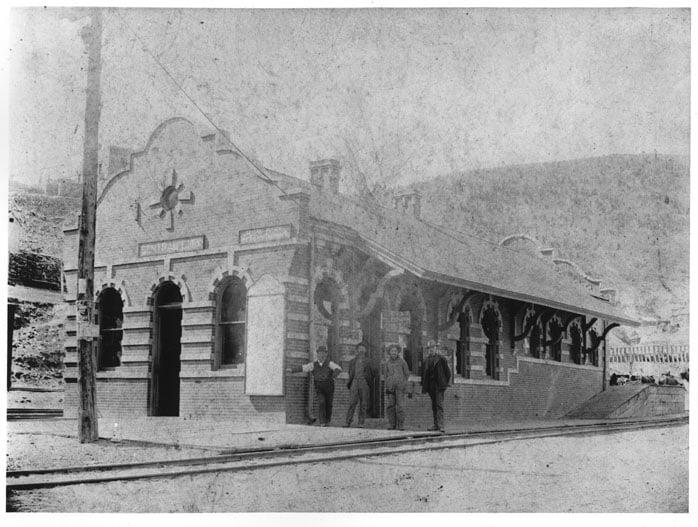

Shay #2 is hauling a train of empty ore cars and a coal car through Prosser Gulch, and about to assault the steep grade up Gunnell Hill. This image came from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection. The operations seemed to be very simple - one or two trains would head up to the mines from Black Hawk in the morning, carrying empty ore cars, coal loads, and occasional other supplies up to the mines. The one or two trains would then distribute the cars to the mines, and pick up loads ( along with empty coal cars, flat cars, and the water car as needed). The third locomotive, or one locomotives that had brought down loads, also would have switched the Black Hawk mills, and interchange with the C&S. Traffic did vary a lot, with many ups and downs, so perhaps some months saw only one train a day, up and down the line. Unfortunately, we just don't documentation to really say. The crews certainly needed good direction on which mines to be worked. Surviving traffic records show that very mines operated continuously from year to year - most seemed to have brief burst of activity, then eventually went dormant or were shut down. So, on any given day, the mines being switched must have varied quite a bit. Crews also needed to keep track of unusual spots of cars - for example, the Columbia Mine loaded ore cars on the main line, until a spur was built (this was discussed in more detail in the previous post), and I speculate other mines could have done so, too, at various times.  Shay #1 is bringing a train of loaded ore cars down Chase Gulch, about to cross Smith Road, in this view from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.  Three shays bringing a train of empty ore cars up Winnebago Hill. This image came from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection. The tram never had more than 3 operational shay locomotives at one time, and so on a typical day, maybe two were in use and one could have been worked on. That said, there is at least one photo showing all three shays bringing a train of coal loads and empty ore cars up Winnebago Hill.  A train of empties ore cars and a flat or coal car, with two shays, blasting up Chase Gulch and nearing Castle Rock, in an image from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection.  The Gilpin Tram had its offices inside the C&S Central City depot. The sign about the right side window states that this is the location of the "General Offices of the Gilpin Tramway Company." So, the superintendent and possibly assistants worked out of here, taking orders from mines and giving orders to crews. The tram did have telephone service from early on, so either written orders were given, or maybe transmitted by phone. The tram did things rather informally, particularly before the C&S purchase in 1906. However, this is only my speculation, as I have not seen written records on this. The written records that I have seen are time sheet records, accounting records, engineer reports on pickups and setouts, and various other documents. No dispatcher books have come to light, but there may never have been one - the tramway was a small operation, and as mentioned, "informal" on a lot things. The crews were union, however. We know this because of a short article in a Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers describing (and with a photo) operations by some of their members. So, the tram seems to be a combination of standard railroad practices and their own methods.  This building may be on Quartz Hill, and may be the building referred to as a the Quartz Hill Depot. Note Shay #4 in the background. i=Image from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection. There is a newspaper report of the Quartz Hill depot, where located not exactly given (other than on Quartz Hill!). I speculate that this may have been located in a somewhat central location near the operating mines to facilitate operations.  This image, also from the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, shows that the tram also had work trains, too. This group seems to be working on stone retaining walls, and was taken on or near the Banta Hill Branch.

Keith Pashina

Narrow-minded in Arizona |

|

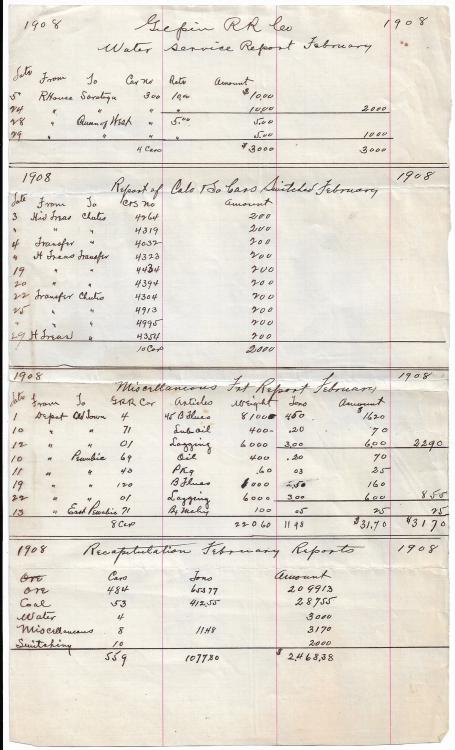

While we are talking about train movement, here is a list of what was happening in February 1908 with dates and destinations. Doesn't appear to be too much going on.

Kevin Fall |

|

Cleaning out old photos and came across this Gilpin photo don't know the location on the tram.One neat item

is the ore sack

|

|

Some Carloadings.

UpSideDownC

in New Zealand |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway: more Haverhill.

|

in Kevin Fall's http://c-sng-discussion-forum.254.s1.nabble.com/Along-The-Gilpin-Tramway-A-Closer-Look-tp20380p20593.html

I'm on the hunt for the location; more to come.   The mountains on the Skyline are : Mestaa’ėhehe Mountain with Chief Mt on the right, so I'm picking this is looking South from high above Russell Gulch(town). GoogleMaps Capture

UpSideDownC

in New Zealand |

Re: Along The Gilpin Tramway: more Haverhill.

|

them thar Hills again....

Russell Gulch Russell Gulch

Denver Public Library L-39 Harry Lake photo

UpSideDownC

in New Zealand |

«

Return to C&Sng Discussion Forum

|

1 view|%1 views

| Free forum by Nabble | Edit this page |